The Heawood Number

The four-color theorem tells us that we can color any map using only four colors, such that no adjacent regions have the same color.

This is true for any map of the world, whether it’s on a globe or laid out flat. But what about maps on other surfaces?

The mathematical formalization of the four-color theorem is: “any planar graph is 4-colorable”. Let’s break down what that means.

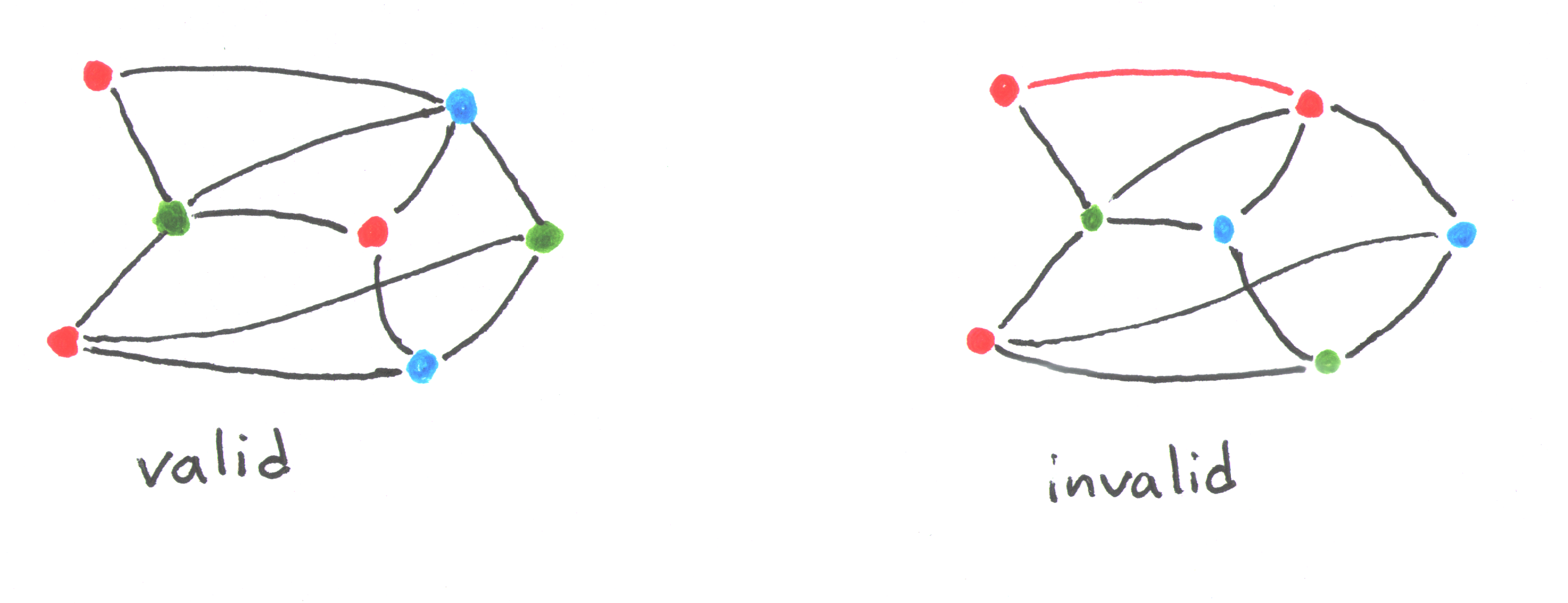

Graph here refers to a collection of vertices and edges, not a plot or a chart. For our purposes, we’ll only consider simple graphs, that is, graphs where a) there is no edge from a point to itself and b) for any pair of points, there’s at most one edge between them. A graph is planar if we can embed it in the plane (i.e., draw it on a sheet of paper) without any of the edges crossing.

A coloring of a graph is a way of coloring the vertices of the graph such that no two vertices of the same color are connected. Note that self-loops make a graph impossible to color, and multiple edges between vertices don’t matter. This is why we concentrate only on simple graphs.

We say a map is \(k\)-colorable if there exists a coloring with \(k\) colors.

So what does this have to do with maps? The problem of coloring a map can be rephrased as a problem about coloring graphs. And since the field is called “graph theory”, and not “map theory”, that’s what we’ll do. Put a vertex for each country, and connect two vertices if the corresponding countries are adjacent. If you can color the map, then the corresponding graph can be colored in the same way. Likewise, if you can color the graph, you can use the same color assignment to color the map.

We’re looking to answer the question: for a surface \(S\), how many colors do we need to guarantee we can color any graph embedded in \(S\)? To do this, we’ll need to make use of an invariant called the “Euler characteristic”.

Euler Characteristic

Euler’s formula for planar graphs says that for any planar graph, \(V - E + F = 2\), where \(V\) is the number of vertices, \(E\) is the number of edges, and \(F\) is the number of faces (including the outside face).

This also applies to graphs embedded on the sphere. Imagine taking a pin and poking a hole in the middle of one of the faces. Stretch this hole out until it is wide enough that you can flatten the entire sphere into a disk. Now you have a graph embedded in the plane. (This explains why we like to consider the outside face a legitimate face.)

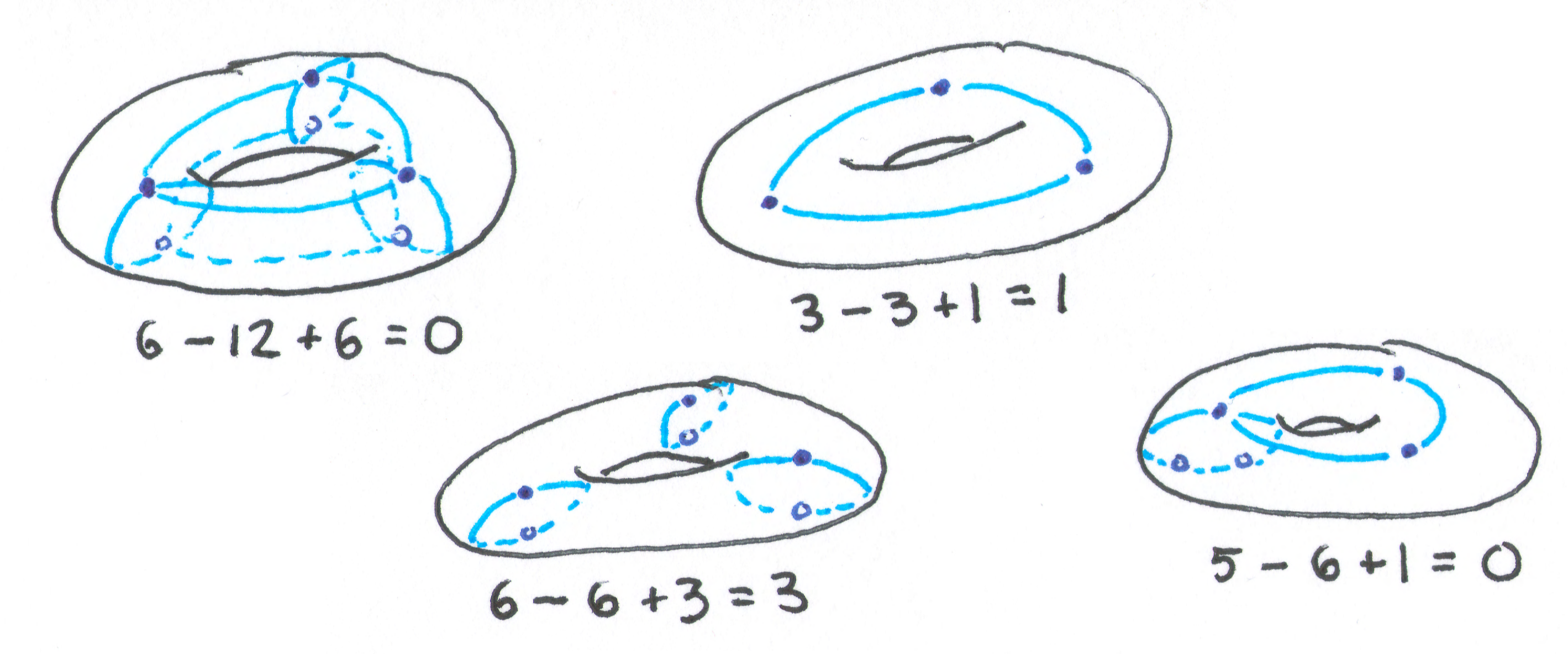

But this does not apply to graphs embedded on other surfaces! Consider the following graph on the torus:

This has 16 vertices, 32 edges, and 16 faces (count carefully, not all of them are obvious). This has \(V - E + F = 0\)! Euler’s formula doesn’t work on the torus, but maybe we can salvage it?

Let’s try some examples:

It seems we usually get \(0\), but sometimes we do get a \(2\), like before. To resolve this, note that in all the examples where we don’t get \(0\), some of the faces have “holes”. If you took the face in the \(3 - 3 + 1\) example and laid it out flat, it’d look like a ring, not a disk.

So we’ll equip ourselves with another definition: if a graph is embedded in a surface, and none of the resulting faces have holes, we call that embedding honest. (This isn’t standard terminology, but you can’t stop me from naming things whatever I want. Try me.) It turns out that if you honestly embed a graph into the torus, you’ll always get \(V - E + F = 0\), no matter which graph you use, or how it’s embedded.

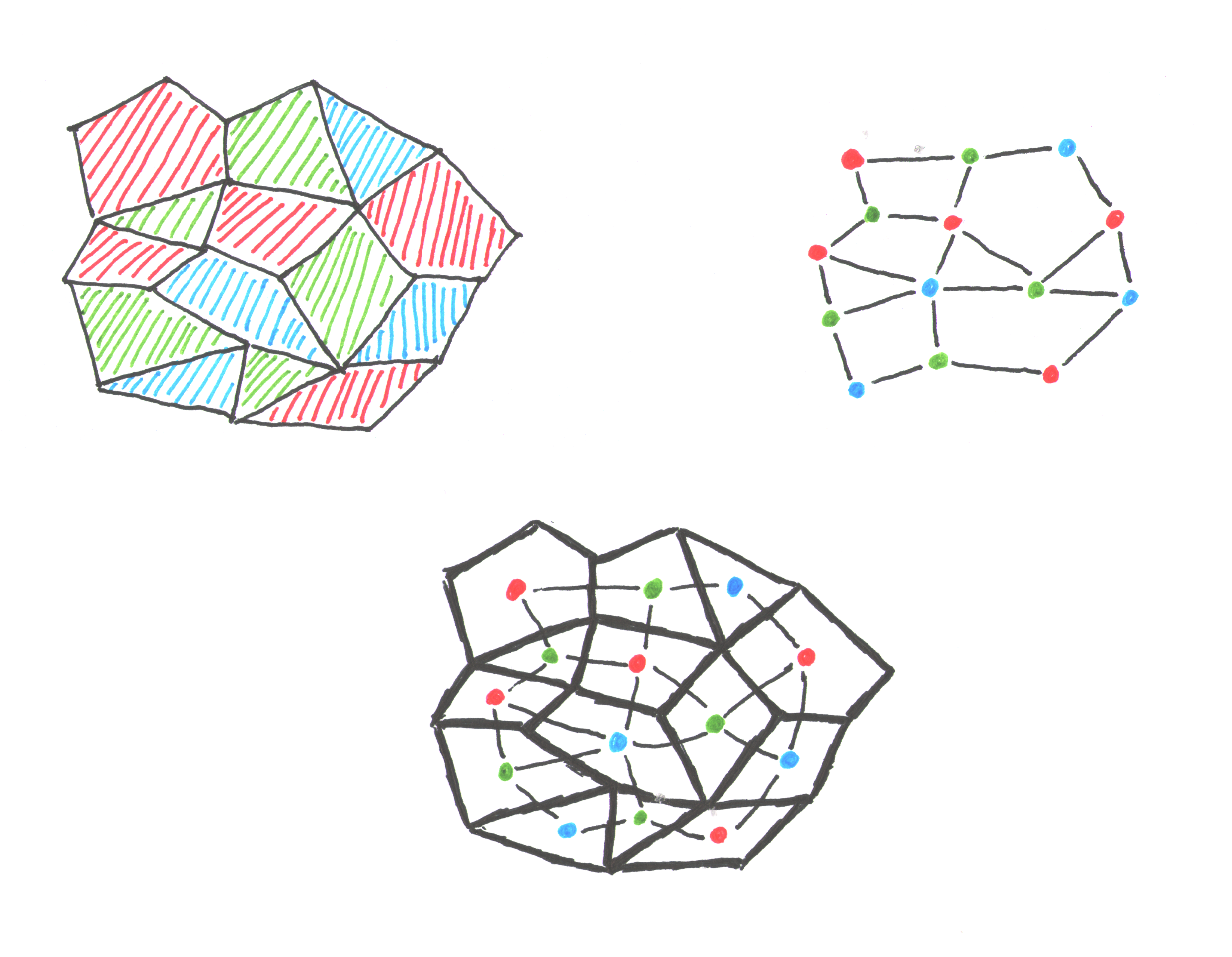

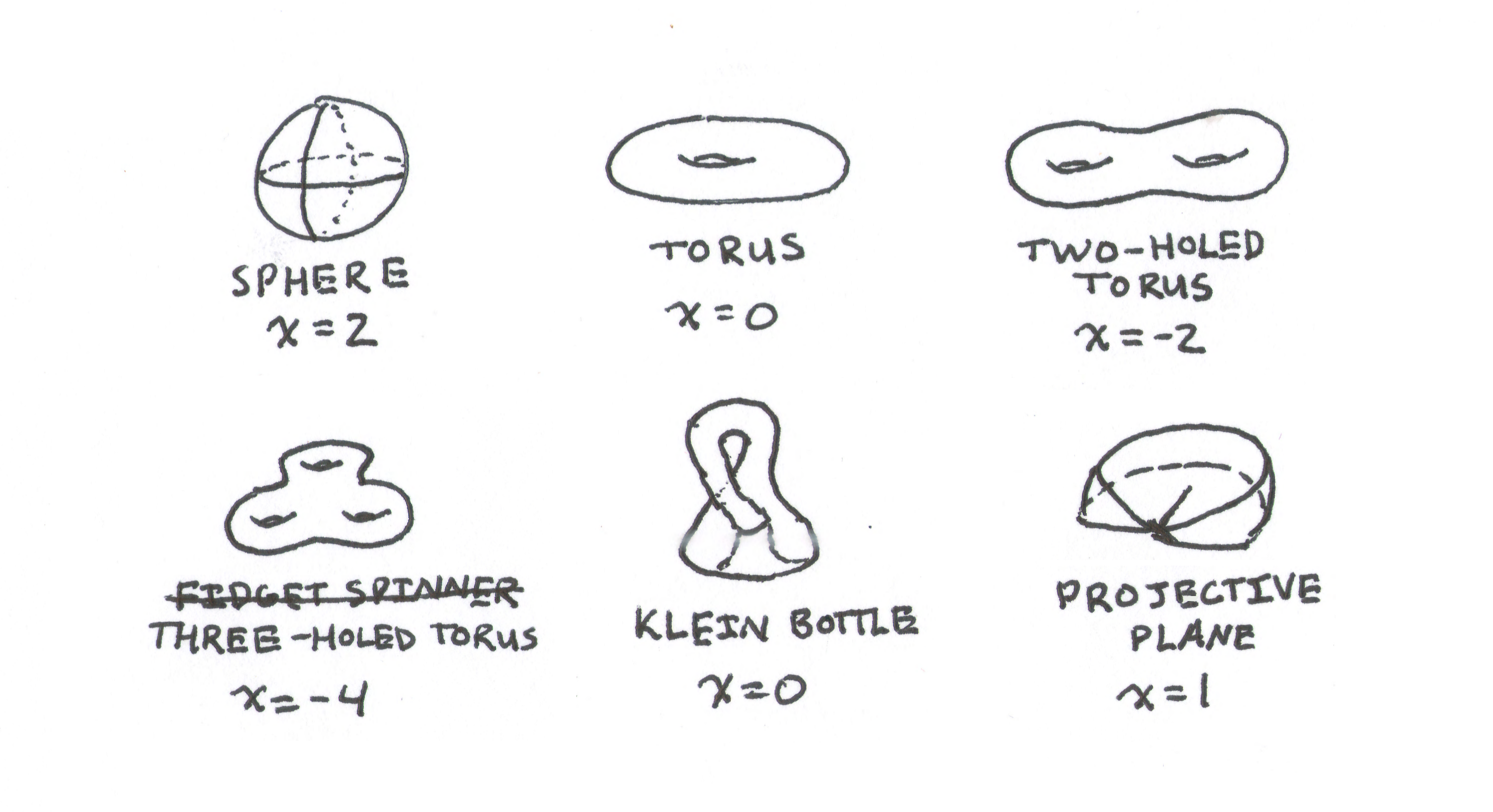

In fact, for any surface \(S\), we have a similar result: there’s a fixed integer \(\chi(S)\) such that \(V - E + F = \chi(S)\), for any honest embedding of any graph. We call this number the Euler characteristic for the surface. For the plane and the sphere, \(\chi = 2\). For the torus, \(\chi = 0\). Here’s some other examples of surfaces and their Euler characteristics:

The Heawood Number

Now we can approach the generalized four-color theorem. Armed with the Euler characteristic, we define the Heawood number of a surface with Euler characteristic \(\chi\) as:

Yeah. That’s… unmotivated.

We claim that any graph that can be embedded on a surface with characteristic \(\chi\), honestly or otherwise, can be colored with at most \(H(\chi)\) colors. For the sphere, \(H(2) = 4\), so our claim becomes the famous Four-Color Theorem, which is Very Hard To Prove (TM). We’ll deliberately exclude that case, like the cowards we are.

The first step is to prove a lemma about the minimum degree of the graph. That’ll get us most of the way there.

Let \(S\) be a surface that isn’t the sphere, and embed a graph \(G\) on it, honestly or not. Let \(V\), \(E\), and \(F\) be the usual, and let \(\delta\) be the minimum degree of a vertex in \(G\). We claim that \(\delta \le H(\chi) - 1\).

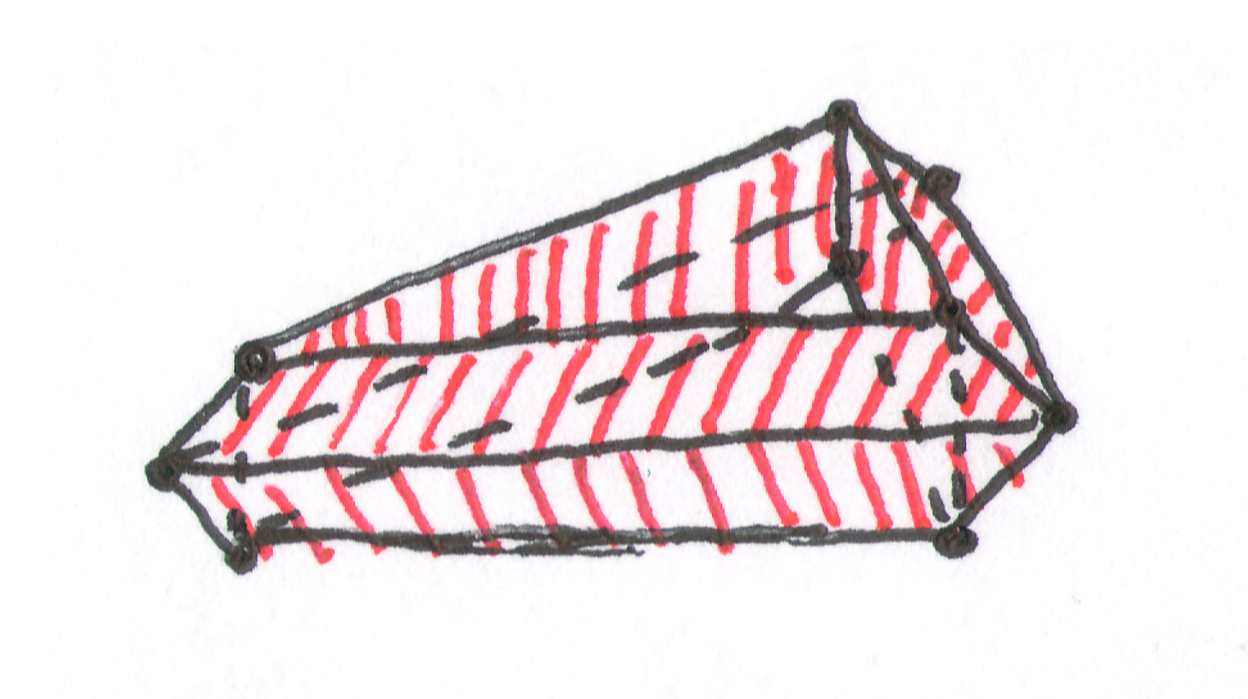

Proof: First, we can extend this embedding to an honest embedding, by adding extra edges to cut up the faces. This can only make \(\delta\) bigger, so if we can prove \(\delta \le H(\chi) - 1\) for this new graph, it was also true for the old graph.

Next, consider the following inequalities, the motivations for which are pulled directly from my ass.

- Since each face has at least three edges, we know that \(2E \ge 3F\).

- The sum of the degrees for all vertices is \(2E\). Thus, \(2E \ge \delta V\).

- A vertex cannot be connected to more than \(V - 1\) other vertices, so \(\delta + 1 \le V\).

Now, from the definition of Euler characteristic, we have:

Here we must split into cases, depending on the sign of \(\chi\).

If \(\chi \le 0\), then we make both sides positive before making use of our last inequality:

Now use the handy-dandy quadratic formula; we get that \(\delta\) is at most \(\frac{5 + \sqrt{49 - 24 \chi}}{2} = H(\chi) - 1\). Boom.

Otherwise, \(\chi > 0\), and by the classification of compact surfaces, we know \(S\) must be the sphere or the projective plane. We’re explicitly excluding the sphere, so \(S\) must be the projective plane, which has Euler characteristic 1. Plugging that in, we get that \(6 \le (6 - \delta) V\). Since the right side is positive, we must have \(\delta < 6\). Because \(H(1) = 6\), we can still guarantee that \(\delta \le H(\chi) - 1\).

So for any graph \(G\) embedded in \(S\), honestly or otherwise, there is a vertex with degree at most \(H(\chi) - 1\).

We’re basically done! We’ll describe an explicit procedure to color graphs on \(S\) with \(H(\chi)\) colors.

Let \(G\) be a graph embedded on \(S\). Our base case is the graph with one vertex; it can trivially be colored. Otherwise, consider \(G\) with \(n \ge 2\) vertices. By our lemma, it has some vertex \(v\) with degree at most \(H(\chi) - 1\). Apply our procedure to the subgraph \(G - v\), coloring it with \(H(\chi)\) colors. Since \(v\) has strictly less than \(H(\chi)\) neighbors, there will be at least one color available for us to color \(v\) with, and so we can color all of \(G\).

Conclusions

We showed that any graph \(G\) embedded in \(S\), honestly or otherwise, can be colored with \(H(\chi) = \left\lfloor \frac{7 + \sqrt{49 - 24 \chi}}{2} \right\rfloor\) colors. The only case we decided not to handle was when \(S\) is the sphere. Unfortunately, that case is much harder. The proof above was discovered in 1890 by Percy John Heawood, after whom the number is named. The Four-Color Theorem wasn’t proven until much later, in 1976, by Kenneth Appel and Wolfgang Haken. And what a controversial proof it was! They managed to reduce the problem to checking a particular property of 1,936 graphs. This wasn’t feasible to do by hand, so they used a computer to check those cases. This was the first computer-aided proof, and it ruffled quite a few feathers.

Secondly, we only established an upper bound on the number of colors we need in our palette. Is there a graph that requires all \(H(\chi)\) colors? Or can we lower the bound a bit? The Heawood conjecture is the claim that we can’t; i.e., that this bound is sharp. And it’s mostly true. In 1968, Gerhard Ringel and Ted Youngs showed that, on almost any surface, you can embed the complete graph on \(H(\chi)\) vertices. Since that graph requires all \(H(\chi)\) colors, that shows the bound is sharp. The only exception is the Klein bottle, where the conjecture predicts \(H(0)=7\) colors are needed, but in fact, \(6\) colors suffice to color any graph.

A maximal coloring of the Klein bottle is shown below: